Some countries have rebellion and struggle baked into their national mythos. Their founding stories are of striving for independence, self determination and fundamental rights against an established ruling class or an occupying force. In this country we’ve a rather different canon for how our rights were won. From King Arthur to the Magna Carta, our myths and history are stories of benevolent rulers graciously bestowing rights upon their subjects.

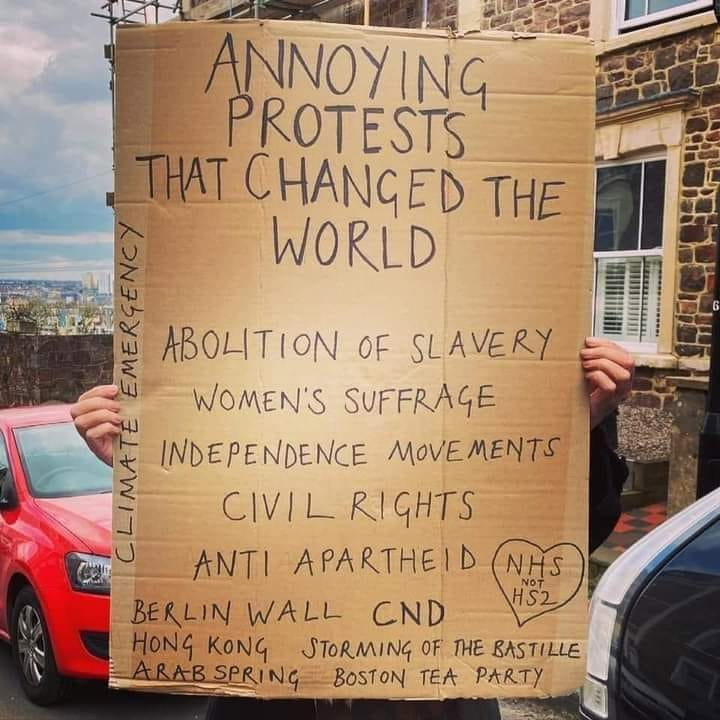

Even those struggles for rights we are taught about are sanitised and dressed up to favour the ruling classes and make them seem benign and beneficent. The Suffragettes – and their violent, controversial but ultimately successful tactics – emerged from decades of ineffective peaceful protest (from the Suffragists). We’re taught that the great William Wilberforce MP abolished the slave trade, ignoring that it would never have even been countenanced if Haitian revolutionaries (amongst others) hadn’t risen up and slaughtered their masters. The St Pauls riots in the 1980s (as well as others around the country) are credited with drawing attention to the racist policing tactics of the day and the reforms that followed, and there are countless others, from the collapse of our global empire to the everyday rights we enjoy without thought.

The myth of perpetual stability and rule of law (or decree) without challenge is one spun by the ruling class to suppress the peasantry. It is now used to make us think we should trust our political leaders and their enforcers with our freedom – a freedom which we have struggled to claw from their greedy hands for generations.

The only people I’d really heard making a fuss about the new Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill before the violent dispersal of Sarah Everard’s vigil were from the GRT (Gypsy, Roma & Traveller) community, whose rights are being even further undermined, and lifestyle targeted, as the bill criminalises trespass. After the violence at the vigil those parts that could be used to criminalise most forms of protest were suddenly in the headlines, and the recent protests in Bristol, also violently dispersed, have kept it there. There’s still not much chance of stopping it passing into law in some form given the Conservative majority, but the impulse to keep pointing out how draconian this raft of legislation is is still worth following through on – public pressure and gathering expert opinion can have a strong influence on changes to the bill as makes progress towards becoming law.

We’ve previously covered some aspects of how the Bill criminalises GRT communities, the homeless, squatters, people out for a walk etc. Last week Lisa wrote an impassioned piece about the pushing of fear for our safety in public spaces, and how this is used to make increased police powers sound reasonable, increasing alienation, and increasing our reliance on organs of the state instead of each other. There are two other main areas of concern with this bill – it drastically curtails our right to protest, and will subject marginalised communities to more stop-and-search and profiling.

The bill lays out several changes in the law around protest, specifically targeting peaceful protests, seemingly because of Priti Patel’s annoyance at not being able to shut down either Extinction Rebellion or Black Lives Matter. (XR and nearly 100 other organisations have issued a statement laying out their concerns, and Greenpeace have a petition with 122,000 signatories and counting.) It increases the restrictions on what kinds of protest can be undertaken without notifying the police, dramatically expands the range of reasons by which they can be denied, and the kinds of activities which can be forbidden by the police. For example they would be able to declare a protest an illegal event “where noise causes a significant impact on those in the vicinity or serious disruption to the running of an organisation”. So that’s pretty much every protest already covered. What’s the point of protesting outside a corrupt business if you can’t do anything that disrupts their operations? Surely, even if you’re not significantly disrupting the day to day work at that premises, then the purpose is to disrupt their business enough that they change their practices or go out of business entirely? It doesn’t even need to be disruptive, it can just cause “serious annoyance or inconvenience” and be shut down. This is thought to be aimed at protestors specifically targeting the House of Commons, and the MPs that work there.

The next paragraph of the bill says says even risking any of the above would be grounds for banning a protest, with just a word from the Home Secretary. We can expect its application to all protests aimed at this increasingly authoritarian government and their mega-rich friends.

Another key change is that under current legislation you can only be charged with breaching the conditions imposed on a protest if you know about them. The new bill makes it so you only have to be “reasonably expected” to know about them. This could mean for instance that if the police shout legal warnings into a protest they could reasonably be expected to have shut up and listened, if you are the police. I don’t think many people who have been on a protest of any kind would necessarily agree. If you break the rules imposed on a demonstration you attend (or other offences, like damaging a memorial) you could get up to 10 years in prison.

Of course, ministers have said that these powers would only be used in extreme circumstances, but maybe you’ve noticed how protestors have in the past been charged under anti-terror legislation, also brought in for very occasional and limited use? Once a power exists it’s always tempting for it to be put to use (it’s the law, right?), and we can’t guarantee that future governments will even make a show of restraint, especially given how the press has shown itself willing to assume that protestors are nothing more than trouble makers out to fight the police.

There’s another aspect of the new bill which still isn’t getting so much attention, despite a summer of BLM protests, and the supposed education of white Brits as to how their privilege makes interaction with the police less risky. After requests from police forces, and against the evidence the bill will once again increase stop & search powers. The government admit there’s no evidence that stop & search powers make communities safer, and they’ve been at the heart of disputes around racist policing with the stats showing it’s disproportionately black people who are stopped – 8.9 times more likely than if you’re white.

Protests in Bristol

Recent events have somewhat confused the conversation over the bill, where fights with the police have been misused as an argument in support of this bill – it’s not even aimed at violent protests and the police already have more than ample power to address violence. The actions of the police and much of the reporting of it, has shown the deeper problems of authoritarian impulses within the state and our press. It’s almost like the press haven’t heard the message coming from communities of colour in the UK – they still swallow the police’s version of events wholesale. Avon and Somerset Constabulary issued statements that included reports of non-existent broken bones and a punctured lung (which they later withdrew) but their story from the night of Sunday 21st March is still largely taken at face value, and their accounts of both Tuesday 23rd March and Friday 26th March are crumbling under increased scrutiny, exposing unprovoked violence inflicted on protestors.

I’d left last Sunday’s protest well before things got out of hand, and not managed to speak to many who were there, so I’ll not comment. I wasn’t there on Tuesday either, but know lots of people who were. Given the events of the previous Sunday they were worried about the prospect of overly aggressive policing, and made every effort to make it obvious they were peaceful. By all accounts Police Community Support Officers and Liaison Officers had established earlier in the day that the protest camp was intending to stay overnight, and leave in the morning. They were there to specifically highlight the impact of the bill on already marginalised GRT communities, and had nothing to do with the violence days before. I’ve not seen any claims of violence directed towards officers that night, but have heard plenty of testimony from those attacked, and even of paramedics on hand refusing to treat a young man bitten by police dogs. Here’s one first hand account from immediately after the protestors were cleared off College Green:

I was at the protest last Friday though, and have the bruises to show for it. There’s plenty of footage now circulating of the police hitting protestors without provocation, and most of the blows I received seemed to be attempts to smash my phone out of my hand, except for the last – in a moment of relative calm I was asking the policeman if he was trying to break my hand or my phone, when one of his colleagues used their baton to hit me in the face.

I wasn’t there to fight the police, and the same goes for the vast majority of the protestors – I was incredibly impressed at the discipline of a crowd, explicitly denied the ability to form any leadership or spokesperson (they’d be risking a £10,000 fine) that had been facing lines of riot police for hours on end, without even a scuffle. I was sat only metres from the front when, with no warning that I heard, the police started marching into the crowd. They used their shields and batons to hit at anyone within reach and push the crowd back. When they reached the point where I was sitting I was forced to my feet. Despite the way Sunday and Tuesday turned out, most people still seemed shocked at the violent dispersal techniques employed, and those who did turn out for a fight were left in running battles, pushed back into Broadmead and St. Pauls.

It may be a bit of a cliché, but my mind keeps going back to Banksy’s Mild Mild West, and its message – we may be chilled out and cuddly in the South West, but if you attack us, our friends, our way of life and our democratic rights, you’ll see a different side.

The School of Activism 2.0, happening 3-18 April, is a curated series of events designed to inspire and empower active citizenship. Relevant to the current unrest, we’d suggest checking out The Strategy and Tactics of a Direct Action (Sat 3 April, 5pm), Know Your Rights: Dealing with Police at Protests (Sun 4 April, 3pm), Who Owns the Land? (Mon 5 April, 7pm) and Rebel History: The Struggle to Reclaim Our Past (Thu 15 April, 7pm).

There is a lot of coverage out there, and I’ve barely scratched the surface of what could be written about the bill and the Bristol protests. Here’s some further reading:

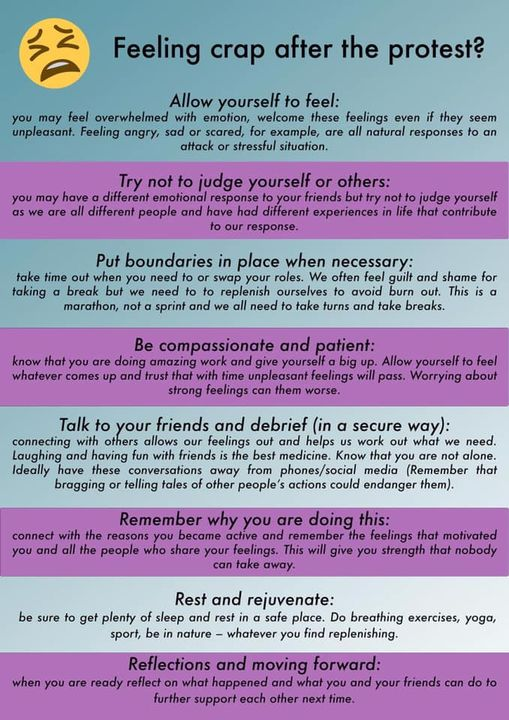

If you’ve been protesting, or are planning on it, here’s some tips for post-protest self-care (click to enlarge) – and even more vital, this PDF from Bristol Defendent Solidarity outlines how they can help if you get arrested, and who to contact if you are.

The race and class implications of the Police, Crime Sentencing and Courts Bill are massive and go beyond the right to protest, from the Institute of Race Relations: Policing in the Brexit State – Back to the 1980s

Local Bristol Cable journalist Matty Edwards writing about the Bristol protests in the Guardian: The police have their version of the Bristol protests. Locals tell a different story. Cable journalists have also been doing great work via Twitter, covering events on the ground as they unfold.

Bristol Defendant Solidarity, set up a decade ago in the wake of the Stokes Croft riots (similarly triggered by overly aggressive policing), are doing great work supporting protestors: Donate to #KillTheBill: Bristol legal support in the streets

For the more visually inclined, our friends Colin Moody and Pitlad have both been capturing incredible images and videos.